Dr Joe Chrisp is a Research Associate in the Institute for Policy Research (IPR) at the University of Bath.

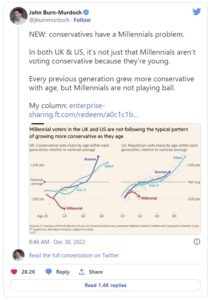

In recent weeks, there has been a lively debate about whether Millennials (those born between 1981 and 1996) are not following the path of previous generations and becoming more conservative as they age. This was prompted by an excellent and widely shared analysis in the Financial Times (FT) and on Twitter by John Burn-Murdoch, which contained the arresting graph below:

In the 2010 UK election, roughly 29% of Millennials voted for the Conservatives. In 2019 this number was closer to 26%. Why then does support for the Tories among Millennials drop so dramatically as they age in the FT graph?

The Y-axis in the graph shows support among generations relative to the national average at a given election. John Burn-Murdoch uses this measure to account for what are called ‘period effects.’ We want to control for the fact that support for the Conservatives changes overall from election to election. If we didn’t do this, then it would look, for example, like the Boomers had suddenly become a lot less conservative in their forties and fifties, when in fact the whole country had swung to the Labour Party in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Similarly, the last 12 years have seen a larger-than-usual proportion of the electorate voting for the Conservatives. Thus, the big drop in John Burn-Murdoch’s graph in effect makes the case that something was preventing Millennials from following the mood of the nation (2015, 2017 and 2019 period effects) and increasing their support for the Tories to the same extent as other generations did as they aged. By extension then, we might assume that they have become less conservative.

However, another way of looking at the graph is to argue that the real aberration is the level of support for the Conservatives from older generations. The over 65s voted Conservative in 2017 more than at any other election in the British Election Study data that we have going back to the 1960s [1]. Because the graph measures support for the Conservatives in each age group relative to the national average, the sharp swing to the Tories amongst older generations pulls up the average, and consequently the Millennials support appears significantly to fall.

Given current polling, you could draw two different conclusions. You could point to the astonishingly low support for the Conservatives among Millennials as evidence of a unique trend of increasing anti-conservativism – and argue that the Tories have a real problem with young people. Or you could say ‘How on earth are 40% of Boomers still planning to vote Conservative after the events of recent weeks, months and even years?’

In short, what we have is an age and/or generational divide in voting and it is not entirely obvious whether the explanation for this is that Millennials or the younger half of the population are less Conservative than you’d expect or that Boomers and older Gen Xers are more Conservative than you’d expect.

This highlights another important thing to understand about the results: the distinction between supporting the Conservatives and being conservative. Voters’ party preferences do not always map neatly onto ideology and social attitudes. There are all sorts of factors that inform party choice and political ‘supply’ can change sharply, particularly parties’ offers to different age groups.

When other researchers have tried to separate out age, cohort and period effects with respect to ideology, they have generally found Millennials in the UK to be economically more right-wing and even more authoritarian on crime and welfare than other generations. Even without controlling for ageing effects, young people are more opposed to tax increases, not particularly fond of a benefits system that has never been accessible to them in the way it once was to earlier generations, and generally less supportive of nationalisation than older people [2], even if they are more socially liberal and pro-immigration. A recently published paper by Tom O’Grady finds this applies to an average of 27 high income countries: young people are more libertarian than socialist in the sense that they are less in favour of greater tax and spending than old people, alongside their social liberalism and support for immigration.

One reading is that the Anglophone phenomenon of Millennials not voting for right-wing parties is as much (if not more of) an age divide as a generational one. We have a political economy in which the interests of older voters are strongly represented and parties have electoral incentives to respond to them: an ageing population, with significantly higher rates of turnout among older voters, and younger voters concentrated in cities where their votes matter less under first-past-the-post.

This means that we might expect Millennials to return to trend soon enough and start voting Conservative again in larger numbers as they age. Of course, this might in part be due to changes in political supply: a Conservative rebrand for ageing Millennials. But today’s Millennials will also probably be tomorrow’s NIMBYs (‘not in my back yard’) when they move out of the cities, inherit their parents’ wealth and start working out their pension entitlements. Interests are intertwined with values and focusing too much on culture war talking points and generational rifts hides some of these fundamental drivers of the age divide in political economy.

[1] The electorate is also getting older, pulling the average in a more conservative direction.

[2] There are generally majorities in favour of public ownership across all age groups.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of the IPR, nor of the University of Bath.

Respond